Pumpkin Production in the Piedmont

go.ncsu.edu/readext?898013

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲Who doesn’t love a pumpkin patch after a few cool, crisp North Carolina fall mornings? When the weather begins to cool off people immediately get in the mood for autumn. Maybe it’s much anticipated relief from our sweltering hot summers we see in North Carolina, but autumn is a highly anticipated season for many. Synonymous with fall is the abundance of pumpkins. Everywhere you turn you’ll find pumpkins – in pies, on porches, in television shows, and even in coffee.

At least traditionally, pumpkins are not commonly grown in the Piedmont of North Carolina on a large scale. Leading in production of this fall weather staple is Illinois, which produced 652 million pounds in 2021 according to USDA data. 2nd place goes to Indiana with a mere 181 million pounds when compared to Illinois. North Carolina produced only about 30 million pounds in the same year and most of this production takes place in the western mountain counties where disease pressure is lower. Still though, many Piedmont growers are interested in pumpkin production on their farms as an alternative crop to add to their operation.

In 2022 Cooperative Extension partnered with the Piedmont Research Station is Salisbury, NC to start a pumpkin variety demonstration. Our main goal was to investigate yield measurements for pumpkin varieties in the Piedmont. Due to higher disease pressure and warmer average temperatures than experienced in the mountains of NC the average weight and yield was expected to be slightly lower than in a growing area more conducive to pumpkins. Complete data sheets from the plot and more can be found further in this article.

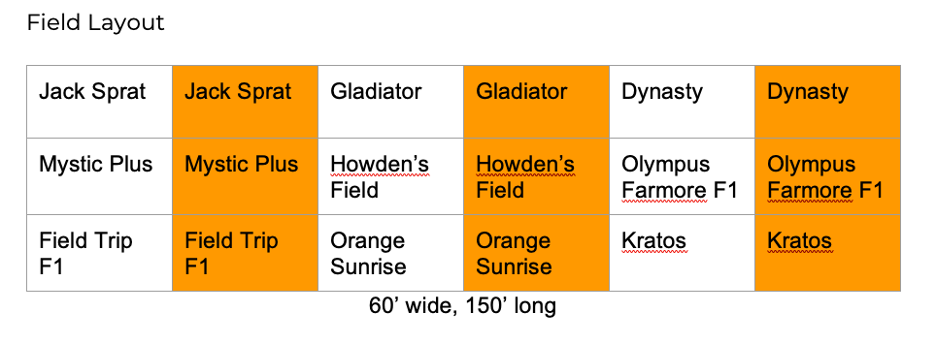

The variety demonstration included 9 commonly grown varieties of jack-o-lantern style pumpkins. 3 of the varieties were small, 3 varieties were medium, and the last 3 were large varieties. Subplots included bare ground and plasticulture to see if there are any appreciable differences between the two production methods. All pumpkins were irrigated using drip irrigation with regular applications of fertilizer through the drip lines. A fungicide spray program along with an insect control program were developed for the plot.

Diseases Encountered:

Powdery Mildew

Downy Mildew

Bacterial Wilt

Common Pests Encountered:

Cucumber Beetle (vectors Bacterial Wilt)

Squash Bug

Pickle Worm

Aphids

Developing a disease and insect spray program for pumpkin is highly recommended. Pumpkins take relatively a long time to mature when compared to other cucurbits like squash or cucumbers. A disease that causes significant damage to the crop will cause severe losses. To develop your own spray program, check out this resource from the University of Delaware Extension. Having a preventative spray product in the program is recommended even before disease detection. Be sure to rotate products in your spray program for resistance management. Once disease is detected by scouting, increase your spray frequencies and/or use more effective products. An air-blast sprayer is typically used by growers to spray pumpkins.

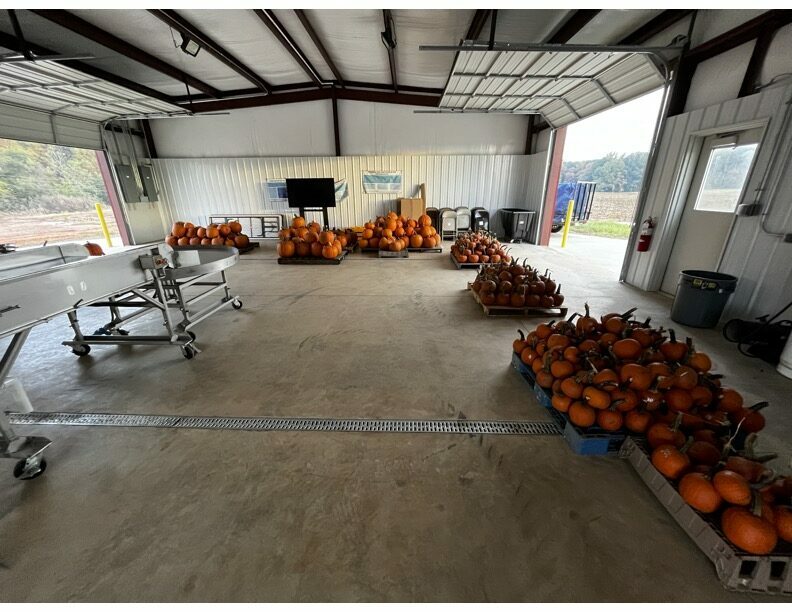

Photo by: Cody Craddock, NC State

Downy mildew will appear in the late season due to its biology. The image above is a photograph of what downy mildew on pumpkin looks like. Once downy mildew is detected in North Carolina it is recommended that growers increase the frequency of their spray applications and spray at the highest allowed rate. Due to the nature of this disease, it is also recommended to apply protective sprays before and after a rain, if possible.

“powdery mildew” by Dmitry Brant is licensed under CC-SA-4.0.

Powdery mildew shows up as a powdery white growth on the tops of leaves. There are many varieties available that have some level of powdery mildew resistance. Selecting these varieties will result in less damage from powdery mildew.

“bacterial wilt” by Spedona is licensed under CC-BY-3.0.

Bacterial wilt is a disease that is controlled by keeping populations of cucumber beetles low, which vector the disease. The disease overwinters in the gut of cucumber beetles and rapidly multiplies in the tissue of the host, clogging vascular tissue which causes wilting. Field observations to look for include plants wilting next to perfectly healthy plants and a dull green appearance. Infected plants will normally recover at night. If using drip irrigation and a plant is wilted, check to see if the emitter is clogged near the symptomatic plant to rule out lack of water.

Acalymma vittatum. By Rudolphus is licensed under CC-BY-2.0.

Young plants are most susceptible to infection of bacterial wilt vectored by cucumber beetles. An application of product that controls Cucumber Beetles should be made at transplant or after emergence. Once the plants have 5+ full leaves the plants are less susceptible, and thresholds can be raised. Cucumber beetles feed on other cucurbits as well so if there are neighboring cucurbits advanced spraying and scouting may be necessary.

Squash bug by Wilifredor is licensed under CC-BY-2.0.

Squash Bugs are like cucumber beetles in that they vector a disease called yellow vine decline. Adult squash bugs themselves are hard to control so most applications of insecticides are aimed at killing the eggs and nymphs. This pest will be in the highest numbers around the field edges, during fruit set, and during blossom.

Pickleworms cause unsightly damage that affects the marketability of the pumpkin and can cause the pumpkin to need to be culled in extreme cases. Pickleworms may be found on the fruits or on the blossoms and they bore holes. Often, these holes have insect frass (excrement) coming out of them. Pickleworms are rarely a problem early in the season.

Photo by: Cody Craddock, NC State

Aphids cause their damage by sucking fluids from the plant tissue and their populations can explode quickly left unchecked. Aphids have many natural predators (lady beetles, parasitoid wasps, etc.) so their populations are partially controlled through biological action. However, at some point in the season you may experience a surge in aphid population in which damage to the plants can occur if left unchecked. Since an appreciable amount of control comes from biological activity its recommended to use insecticides that will preserve those natural enemy populations. There are many systemics insecticides labeled that do not affect the natural enemy populations as heavily.

Description of the demonstration plot:

Our demonstration plot had a total of 0.38 acres of land in production. 9 varieties were trialed and using bare ground and plasticulture production systems. All the varieties grown were trailing or semi-trailing pumpkins which need more space than a bush-type variety. Row spacing was 10ft on center with plants spaced 5ft from each other in-row. Total plant population was ~900/acre.

This table (above) represents the field along with subplots. White rows represent plastic rows and orange rows represent bare ground rows.

Data Points Collected:

We collected the following data for the pumpkins in this demonstration plot: circumference of pumpkin, stem length, stem diameter, weight, subplot total count, subplot total pounds, subplot total volume. Below is more information on why each measurement was taken.

Circumference the circumference of the pumpkin was used collected to calculate the volume of the pumpkin.

Stem length: when selling pumpkins in a retail market like many Piedmont producers do having a pronounced stem (sometimes called handle) is required. Consumers look for pumpkins with nice stem length and attachment.

Stem diameter: another quantitative measurement for the stem. Larger diameter stems often are connected to the pumpkin better.

Weight: weight was collected to analyze differences in bare ground subplots and plastic subplots, but also measure varietal performance against each other.

Total count: total count was collected to analyze differences in the number of pumpkins produced in subplots.

Total pounds: the weight of each pumpkin measured was added up to determine the total pounds of pumpkins produced per subplot.

Total volume: the total volume of pumpkins produced was also determined per subplot. This measurement is useful for producers who sell “by the bin”.

Plastic vs. Bare ground Performance:

It’s not uncommon knowledge that you will have higher yields when crops are grown on plastic but take a moment and consider why that is. For starters, you’ll have better control of moisture in the soil. Using plastic requires that you also use irrigation drip tape which precisely applies water to the roots and the plastic allows less soil evaporation. Another advantage is better weed suppression. The plastic is a physical barrier that makes it tough for weed seeds to penetrate through. Weeds shade out plants and take away nutrients. One more advantage is the lack of soil contact. When it rains or crops are irrigated with overhead, soil splash is the source for some of the diseases encountered through the season.

Our pumpkin fields saw an overall 54% increase in overall yields, but when you take a closer look, an interesting trend emerges. The small varieties saw an increase in yields (on a weight basis) of 61.5% when grown on plastic instead of bare ground, medium varieties saw a 50.5% increase, while large varieties saw just a 10.2% increase. Very similar numbers arise when yield is measured on a volume basis. Further research may investigate this trend by comparing additional production methods including no-tillage (crop mulch system).

Economics of Pumpkins:

Most growers in the Piedmont will be selling retail pumpkins at farmers markets or directly off the farm and not “by the bin”. By the bin refers to the large bins seen in grocery stores in the fall that large scale producers in the mountain counties may sell by. Retail sales most commonly are either by the pound or by the size. However, size can be subjective to personal judgement. The farmer is going to tend to think the pumpkin belongs in the larger category while the customer will tend to believe it belongs in the smaller category. For this reason, some growers chose to sell by the pound.

Penn State Extension has excellent crop budget analysis worksheets available to download. The budget analysis sheets from Penn State Extension are separated by no-till and plasticulture so be sure to download the one best for you. To use a crop budget worksheet, you’ll need to have some basic numbers to enter in the costs correctly. For additional yield data that was collected in NC look at this 2019 Pumpkin Cultigen research at the Upper Mountains Research Station.

Download Data:

Pumpkin Data October 6th Harvest

Additional Readings: